At a recent conference, I posed a simple question to a panel of preeminent AI researchers, entrepreneurs, and economists: “What is the finish line for the AI race between the U.S. and China, and how do we know if we’ve crossed it?”

During World War II, the finish-line for the Manhattan project was singular: create an atomic bomb before the enemy could. During the Cold War, the goal was also concrete: land a man on the moon before our opponents. In both of these cases, the finish-line was measurable and definable.

I believe that political metaphors are extremely powerful, especially in a democracy, for shaping opinion and promoting action. However, framing the field of AI research as a “race” between the U.S. and China is misleading because the “finish line” is neither quantifiable nor defined. Without a crystal clear objective, we risk having rival nations or profit-driven interests dictate the pace and direction, potentially sidelining the public good.

AGI as the Finish Line

The expert panel provided me with two ideas for the finish line of the AI race. The first is AGI, or Artificial General Intelligence. AGI describes AI systems with advanced capabilities across a variety of domains. It is notoriously difficult to define and is the subject of ongoing debate, with academics, entrepreneurs, and policymakers all defining it differently.

One definition is that AGI can be thought of as “generally intelligent” software, or software that can “outperform humans across the board.” This definition is still nebulous and promotes a few questions. When we say “across the board,” are we talking about primarily cognitive tasks? Should the AI system be better than the average human, or all humankind? Right now we are using standardized tests like the SAT or GRE to compare general intelligence, but is this the right way to define human “intelligence”?

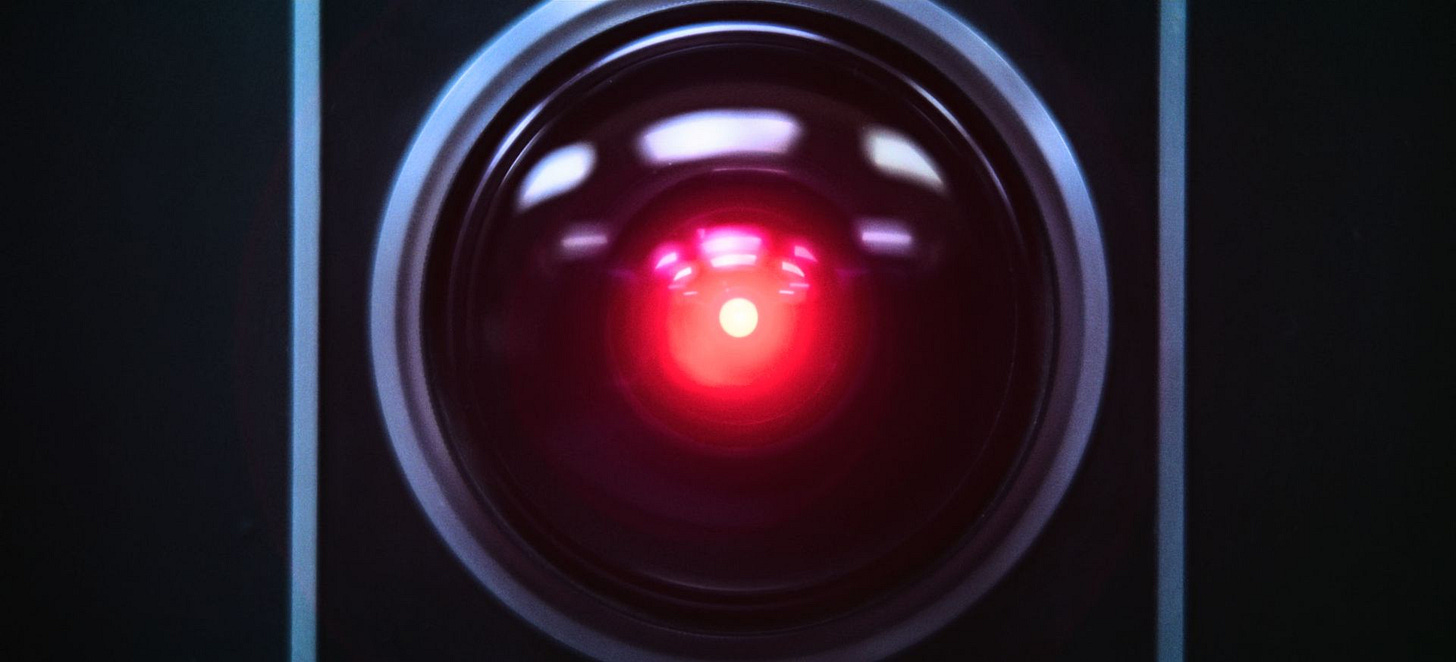

In the absence of a clear definition for AGI, Hollywood has stepped in to provide a mental model for many through movies like 2001: A Space Odyssey, Terminator, and Ex Machina, among others. AGI is essentially depicted as a conscious, God-like being: omniscient, omnipotent, omnipresent. Sometimes it is benevolent, but it is more often evil. Unfortunately, this is what most laypeople think of when we talk about AI.

This definition of AGI is understandably alarming. It makes us nervous because it poses an existential threat to our intelligence, sense of uniqueness, and even physical safety. Many are afraid that AI will exterminate mankind, either accidentally (see the paperclip maximizer thought experiment), or through consciously concluding we should not exist. While there is robust debate on whether or not this type of AI could even exist in the near-term (I’m a skeptic), it is ultimately not helpful as a destination because no one knows what it looks like, and the most prominent depictions we have are concerning.

Returning to the metaphor, if it is unclear what AGI is and if we have achieved it, how do we know if we actually “win” the race? The definitions are so ill-defined and constantly changing that one can never “win” because the goalposts keep moving. Indeed, AGI can be at best thought of as “what we haven’t built yet” and at worst a Terminator-like being.

There is No Finish-Line

Alternatively, some argue that there isn’t a finish line at all—that we should compete simply to stay ahead. This implicitly acknowledges the shortcomings of the metaphor, for if there is no end-goal, why are we competing?

The “race” thus takes on existential robes and can be seen as a battleground between the capabilities and leadership of China and the United States. Indeed, the rhetoric has shifted militantly as CEOs describe the competition as an AI Arms Race or an AI War. But without a clear goal, we end up constantly comparing notes: how do our models stack up? How much are we investing compared to our rivals? Rather than focus on the outcomes of these advancements, we are distracted by symbolic wins.

An Alternative Destination

Neither of these destinations are compelling. Competing for competition’s sake is not powerful enough to promote the investment in technology required to promote prosperity in the United States, and AGI is too often a fantastic fiction promoted by CEOs of AI companies hoping to drive sales and investments.

As we’ve seen with the recent wars in the Middle East, without a clear finish-line or end-state, we risk endless, direction-less investments. With the recent announcement of a $500 billion investment into AI infrastructure through the Stargate Project, it is imperative that we better define the destination of our efforts. I propose that we instead focus on a specific, related field and articulate a clear vision around energy.

As AI’s computational demands continue to soar, data centers alone are becoming massive energy consumers. Without a sustainable source of abundant power, we risk environmental damage or stagnating innovation. This is where nuclear energy could step in.

In the 1950s, Lewis S. Strauss, then-chairman of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, famously envisioned a future powered by limitless, affordable nuclear energy, “too cheap to meter.” This abundance of energy would have far-reaching effects, with the International Energy Agency noting that “energy efficiency improvements are not just a cost-saving measure; they also act as a catalyst for enhanced productivity and technological innovation.”

Beyond powering massive data centers for AI research, cheap energy could enable large-scale desalination to address global water shortages, spur breakthroughs in carbon capture technologies to combat climate change, and dramatically reduce manufacturing costs in energy-intensive industries. It could also open doors to new frontiers—such as more viable space travel, improved agricultural production (through vertical farming or greenhouse operations), and the advanced materials research needed to create next-generation products. In short, an era of abundant, affordable energy would not only bolster existing sectors but also pave the way for innovations that are currently constrained by energy scarcity.

Nuclear energy can provide the tangible finish line AI currently lacks. By investing in nuclear power breakthroughs—tracked through clear metrics like price, safety, and output capacity—we can fuel AI innovation in a way that benefits everyone. This approach provides the clarity and cohesion missing from AI’s moving goalposts, setting the stage for real prosperity and technological advancement in the decades to come.

Unlocking the next stage of human development requires manipulation of massive amounts of energy, and I definitely agree we should be all in on the utilization of nuclear energy. I'm all for trying to use AI to help achieve technological breakthroughs, but the largest hurdles preventing nuclear energy from achieving mass adoption are economic & regulatory in nature. Unless we can train chatGPT to convince Congress to push legislation or the President to subsidize markets, incentivize producers/buyers, construct infrastructure, etc., I can't imagine how effective employing AI is for advancing the nuclear energy cause.

The most practical instance? Identifying new ways to store/dispose nuclear waste, improve process efficiency, or advance basic academic research. I just asked chatGPT (trying to ignore the gallon of water used to answer my question)"what is the best way AI can be used to improve mass adoption of AI". 4 of top 5 answers economic/regulatory in nature. Maybe we can assemble a crack team of materials science engineers in a mini-nuclear power plant, call it SunGPT, and get Sequoia to put 50M behind it? I'm sure if we flash the stanford logo enough times on our slide deck we'll hypnotize them before they can tour the facility.